Best Practices for Using ConcurrentDictionary

One of the goals in concurrent programming is to reduce contention. Contention is created when two (or more) threads contend for a shared resource. The performance of synchronization mechanisms can vary considerably between contended and uncontended cases.

The .NET Monitor class (used by C#’s lock keyword) provides a hybrid synchronization solution that is highly optimized for the uncontended case. When a thread requests a lock for an object that no other threads currently own, the CLR marks this using a few relatively simple processor instructions. However, when another thread requests the same lock, it must be blocked. Only then a kernel wait handle is created, making an expensive user-to-kernel call. It is obvious we should strive for such locks to be as uncontended as possible. Throughout this article, unless otherwise noted, the locks I’ll be referring to are Monitor locks.

Before .NET 4 when we wanted to synchronize access to a dictionary we could:

- Implement the

IDictionary<TKey, TValue>interface and wrap each method with a lock - Encapsulate the required dictionary operations in a class, and protect each method with a lock

- Same as the above options, only using a reader/writer lock

These approaches suffer from some or all of these problems:

- No multiple readers

- No multiple writers

- No complex atomic operations

- No thread-safe lock-free enumeration

- Many methods throw exceptions if they don’t succeed (and this can be highly expected in a multithreaded environment)

Due to all of these, they do not scale up very well. That means that if we add more CPU cores, we (somewhat counter-intuitively) will not get better performance (and sometimes even worse), because the threads would be busy dealing with the added contention.

So how does ConcurrentDictionary do better?

- Reading from the dictionary (using

TryGetValue) is completely lock-free. It uses memory barriers to prevent corrupted memory reads. - Enumerating the dictionary (using

GetEnumerator) is also lock-free, but does not guarantee a “moment in time” snapshot of the dictionary (i.e. the enumeration may change after callingGetEnumerator, but we usually wouldn’t care about that in multithreaded environments). - Writing to the dictionary uses multiple lock objects (also referred to as fine-grained locking) which considerably reduces the chance of contention.

- By default, the dictionary creates 4 times the processor count of lock objects (in .NET 4.5 this number also grows dynamically as the dictionary fills up - another scale up benefit).

- You can also specify a fixed concurrency level (i.e. number of locks) via a constructor parameter (but normally you shouldn’t as you lose the dynamic growing).

- Each object is assigned a lock according to its hash code. Usually a single lock object is responsible for several buckets.

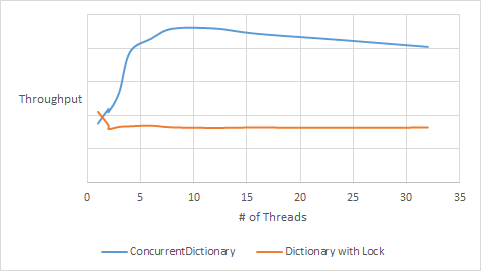

I’ve adapted a small test program that was used by the authors of an excellent book I’m reading, Java Concurrency in Practice, to C#. The tests runs N threads in a tight loop, trying to retrieve a value from the dictionary. If it exists, it attempts to remove it with a probability of 0.02; otherwise it attempts to add it with a probability of 0.6.

You can see the results below (run on an 8-way machine). Concurrent dictionary is a clear winner here, and it’s no wonder.

There are, however, a few things to keep in mind when using ConcurrentDictionary.

Acquiring all locks

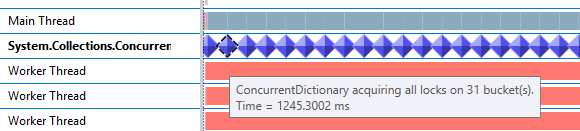

Some operations in the dictionary cause it to acquire all the locks at once. We can see this clearly in Visual Studio 2012’s Concurrency Visualizer (which uses ETW events):

This happens when you call either of these methods:

- Count, IsEmpty properties

- Keys, Values properties (which create a snapshot of the dictionary keys/values)

- CopyTo (explicit

ICollectionimplementation) - Clear

- ToArray

Aside from Clear and possibly ToArray, all of these methods have little use in a concurrent environment.

-

The count could be invalid as soon as the call from the method returns. If you want to write the count to a log for tracing purposes, for example, you can use alternative methods, such as the lock-free enumerator:

dictionary.Skip(0).Count()Skip(0)is required here because LINQ is optimized forICollections, and will attempt to use theCountproperty when it is available (Select(item => item)would work just as well, butAsEnumerablewould not.) -

The same goes for Keys and Values properties, use a LINQ select:

dictionary.Select(item => item.Key)

I’ve seen too many developers fall into this trap and thus losing nearly all the advantage of ConcurrentDictionary.

Personally, I blame MSDN for not clarifying this further. If you look at the Count property remarks, you’ll see a vague comment stating that “This property has snapshot semantics”. This comment is even missing from some of the other members. Thankfully the developers of .NET’s concurrent collections made the situation better by exposing ETW events. So use the Concurrency Visualizer as part of your regular performance testing.

Value factories are not guaranteed execution protection

In the beginning of this article, I said one of our goals is to reduce contention. So it should come as no surprise that the designers of ConcurrentDictionary chose not to run the value factories within the lock. When you supply a value factory method (to the GetOrAdd and AddOrUpdate methods), it can actually run and have its result discarded afterwards (because some other thread had won the race).

If you need to have execution protection, use Lazy<T> (i.e. ConcurrentDictionary<TKey, Lazy<TValue>>). This is a thread-safe class that ensures (depending on its mode) the factory will run once and be safely published (if the value takes a long time to calculate, you can even consider using Task<T>).

If you need to know whether GetOrAdd actually added a value, you can use this implementation from the .NET Parallel Programming team.

It’s not just another IDictionary<K, V>

While ConcurrentDictionary implements this interface, it is not well-suited for concurrent use. There are no “try” methods for write operations. Instead exceptions are thrown for cases that are quite unexceptional for a concurrent program. Moreover, it does not provide complex atomic operations, such as get-or-add and add-or-update (for more details, see this post by the PFX team.)

If you do choose to expose a dictionary (a questionable move by itself), you probably don’t want to hide the fact you’re using a concurrent dictionary from your consumers, so they may use it correctly and reap all its benefits.

Conclusion

Use concurrent dictionary well, and your code will be more scalable, without any special effort on your part.